Pipa

The pipa (琵琶) , sometimes referred to as the Chinese lute, is a plucked string instrument with origins dating back to the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). It shares a common ancestor—the oud—with the European lute and the guitar. According to Eastern Han (25–220 CE) scholar Liu Xi 劉熙 (birth and death years unknown), the name pipa has onomatopoeic origins: pi refers to a downstroke and pa to an upstroke. However, scholars have acknowledged a long-standing theory that the word pipa (琵琶) may derive from barbat, the Persian lute. Earlier scholars, such as Laurence Picken (1955), regarded this etymology as speculative and advised caution in adopting it without stronger evidence. Ethnomusicologist John Myers similarly revisits the theory in The Way of the Pipa (1992), noting its plausibility.

Historically, pipa was a generic term for all straight-necked, lap-held plucked instruments (Picken 1955). Scholars agree that the curved-neck pipa likely arrived in China via the Silk Road between the Han and the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589 CE) (Li 2007; Sotomura 2010; Zhao 2003). This design eventually became dominant and flourished during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), when the pipa became a prominent instrument in court and urban music culture.

In the 20th century, the pipa was restructured to accommodate Western tuning systems and concert environments. Modifications such as additional frets, a larger body with thinner wood, and nylon-wrapped steel strings have increased both the instrument's chromatic range and acoustic projection, aligning it with concert hall standards—an environment in China shaped historically by Western classical music's association with modernity and national development (Yang 2007: 3–8).

Traditional Pipa Music

Chinese classical music has historically favored programmatic expression. Rather than pursuing abstract musical forms, Chinese compositions often center on “nonmusical” or “extra-musical” ideas, typically conveyed through descriptive titles and poetic narratives. As Kuo-Huang Han explains, “it is uncommon to find Chinese instrumental pieces without some sort of descriptive or suggestive title,” and the Chinese tradition strongly emphasizes portraying scenes, stories, or emotions through instrumental music (Han 1978: 17–18). This cultural preference is rooted in a broader Chinese aesthetic that values literary and pictorial associations in all art forms (Han 1978).

Traditional pipa music reflects this programmatic tradition. While there are multiple ways to classify pipa pieces: by tempo, formal structure, or schools, the most enduring and widely used system is based on musical style and expressive content. Scholars typically divide the repertoire into three categories: Wenqu (lyrical tunes), Wuqu (martial tunes), and Wenwuqu (mixed martial and lyrical tunes) (Wei-hua Liu 劉芛華 2021).

Wenqu 文曲 – Lyrical Tunes

Wenqu (文曲) refers to lyrical, poetic pieces that emphasize melodic beauty, subtle ornamentation, and expressive nuance. These works often depict scenes of nature, emotions, or literary stories.

Examples: High Moon 月兒高, River Flowers in Moonlight 春江花月夜

River Flowers in Moonlight has a rich and layered history shaped by musical reinterpretation, poetic resonance, and changing performance contexts. Its earliest known title was Xiyang Xiaogu 夕陽簫鼓 (Flute and Drum at Sunset), referenced in Jin Yue Kaozheng 今樂考證 (Jin Yue Kaozheng: A Study of Modern Music), a 19th-century musicological work by Yao Xie 姚燮 (1805–1864) (Liu 2021; Chen 2022).

In 1895, pipa musician known for compiling Pipa Xinpu 琵琶新譜 (New Score for the Pipa), Li Fangyuan 李芳園, significantly revised the piece and renamed it Xunyang Pipa 潯陽琵琶. The new title invoked the city of Xunyang 潯陽, now Jiujiang 九江, a site famously referenced in Bai Juyi’s 白居易 poem Pipa Xing 琵琶行 (Song of the Pipa), known for its emotional encounter with a pipa player. This poetic association likely influenced the renaming and interpretive mood of the piece. Li’s student Wang Yuting 汪昱庭 further refined the work, retitling it as Xunyang Yeyue 潯陽夜月 (Moonlight Over Xunyang) or Xunyang Qu 潯陽曲 (Xunyang Melody), emphasizing atmosphere and poetic allusion (Chen 2022).

In 1925, the piece underwent a major transformation when Liu Yaozhang 柳堯章 of the Shanghai Datong Yuehui 上海大同樂會 (Shanghai Datong Music Society) arranged it for a sizhu si zhongzou 絲竹四重奏 (silk and bamboo quartet), renaming it briefly as Qiujiang Yue 秋江月 (Autumn River Moon). Soon after, Zheng Jinwen 鄭覲文 retitled the ensemble version as Chunjiang Huayueye 春江花月夜 (River Flowers in Moonlight), directly referencing the Tang poem of the same name by Zhang Ruoxu 張若虛, whose themes of nature, ephemerality, and longing paralleled the expressive spirit of the music (Han 1978; Chen 2022).

This final renaming was both poetic and strategic: as Han notes, the new title attracted broader audiences through its literary beauty and evocative imagery (Han 1978: 26). River Flowers in Moonlight is thus not merely a single composition, but a living artwork—transformed across generations by personal vision, poetic imagination, and evolving performance practice.

Musically, the piece paints a tranquil picture of boatmen returning at dusk, blending natural imagery with personal reflection. Its lyrical style aligns with the Jiangnan sizhu 江南絲竹 (Jiangnan silk and bamboo) aesthetic, using a graceful pentatonic melody to evoke tenderness and nostalgia, making it one of the most expressive and enduring works in the pipa repertoire.

| 1. Dance of the Yi Tribe | 6:53 |

| 2. Spring Sun on Snow | 3:27 |

| 3. Great Wave Washes Sand | 5:02 |

| 4. Falling Snow on Evergreens | 6:55 |

| 5. Plum Blossoms | 4:56 |

| 6. Send Me a Rose | 1:49 |

| 7. Spring on TianShan | 3:36 |

| 8. River Flowers in Moonlight | 8:31 |

| 9. Hurrying to the Flower Festival | 4:40 |

| 10. Lightening in Drought | 1:58 |

| 11. Ambush from All Sides | 6:36 |

| 12. Palace Dancers in Jade Robes | 6:48 |

| 13. High Mountain Water Flowing | 2:38 |

| 14. Jasmine Flower | 1:47 |

Cantonese Music

Cantonese music encompasses a rich diversity of styles, including Cantonese opera 粵劇, narrative singing traditions such as naamyam 南音 (tune of the South) and mukjyu 木魚 (wooden fish, name of a wooden percussion instrument crucial to the singing tradition), and contemporary genres like Cantopop. Each form reflects the cultural and historical evolution of Hong Kong and southern China, blending traditional elements with modern influences. The rise of Cantopop and exposure to Western entertainment in the second half of the twentieth century have ushered a decline in the more traditional art forms in Hong Kong.

Performance at LockCha Tea House

Wan Yeung (pipa), Tony Law (qinqin), Tam Sheung-chi (yehu & vocal) performing naamyam at LockCha Tea House in Hong Kong in 2015.

Cantonese Opera

Westerners and even many young Cantonese speakers often dismiss Cantonese operatic songs as little more than high-pitched screeching. But a closer look reveals a richly layered art form embedded with cultural tradition, improvisational skill, and historical depth.

Practices in Cantonese opera have evolved differently in Hong Kong and mainland China, shaped by distinct political and social conditions. Political tensions restricted the exchange of artists and information across the border, since the two regions were ruled by governments with strained relations. In Hong Kong, where Cantonese opera developed primarily in response to market forces rather than state directives, the genre has retained a highly improvisatory character. Classic works, such as the ritualistic playlets that have become “essential routines” 例戲 in ceremonial performances (Chan 2020), still rely on <1>taigong 提綱, a skeletal script format. These outlines require performers and musicians to compose the lyrics, music, and choreography themselves (Yeung 2024).

Although professional opera and operatic song performances declined after the 1960s (Lai 2010; Yu 1987), amateur interest grew. By the end of the twentieth century, community-based operatic song clubs had become increasingly popular. In 2007, there were an estimated three to four hundred such clubs active in Hong Kong (Lai 2010), demonstrating the enduring grassroots vitality of the form. Data from the Hong Kong Annual Arts Survey Report 2018/2019, published by the Hong Kong Arts Development Council, further illustrates this persistence. Between April 2018 and March 2019, there were 1,857 xiqu 戲曲 performances, of which over 1,810 were Cantonese opera or operatic song concerts organized by avocational artists. In contrast, the same period saw 3,015 variety and pop shows and 2,670 non-xiqu theatrical productions. Yet xiqu attracted the highest total audience numbers, drawing approximately 930,000 attendees, more than any other performing arts genre in Hong Kong.

While professional troupes usually organize full-scale opera productions, avocational artists tend to organize operatic songs concerts. The concerts frequently feature performances of operatic songs while standing up without complex choreography, a style known as “standup singing” 企唱 (kei ceong in Cantonese, qi chang in Mandarin), and opera excerpts 折子戲 (zit zi hei in Cantonese, zhe zi xi in Mandarin), where performers acted out elaborate choreography in full Cantonese opera makeup and costumes (Yeung 2024).

Classic Cantonese Operatic Songs Concert at Yau Ma Tei Theatre on May 27, 2015

Western Music

The modern pipa, with its chromatic fretting and strong projection, allows for deep collaboration across genres. Here are examples of Wan Yeung's Western projects, especially the pipa-guitar duo formed at UC Irvine with George Macias.

Wan Yeung (pipa), George Macias (classical guitar)

Wan and Macias

Formed while music students at UC Irvine, Wan Yeung and George Macias formed a pipa-guitar duo exploring musical bridges across cultures and timbres. George began guitar at 14 under his father, studied with Richard Flores, and completed degrees under Kerry Alt and John Schneiderman.

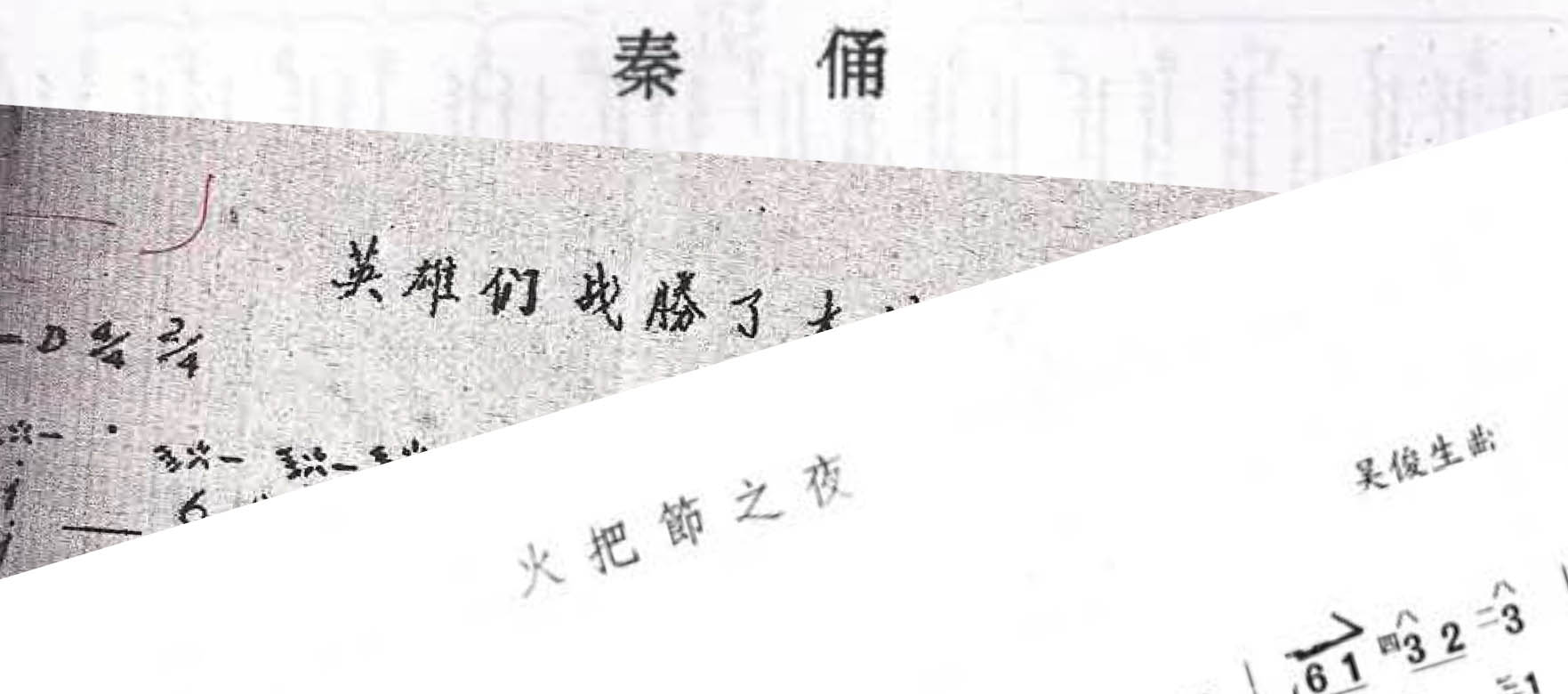

Contemporary Music

The pipa’s versatility finds new voice in contemporary music, whether through cross-genre collaborations, world premieres, or commissions that expand the instrument’s sonic possibilities. Wan also plays in contemporary chamber settings, working with composers and musicians to bring new works to life.

Early on after the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC), government officials encouraged pipa musicians to compose new music for the instrument (and other musicians for their respective instruments). As a result, the standard pipa repertoire consists of mostly compositions, whether based on pre-existing tunes or not, by pipa musicians in the middle and the late twentieth century (personal interview with Wu Junsheng, summer 2016). These compositions include Hurrying to Flower Festival by Ye Xuran, Dance of Yi Tribe by Wang Huiran, Little Sisters on Grassland by Liu Dehai, and Night of Torch Festival by Wu Junsheng. This tradition carries on. But in addition to pipa musicians, composers also contribute to the growing pipa repertoire.

Dance of Yi Tribe

Dance of Yi Tribe incorporates melodies from folk music of the Yi Tribe, including Haicai Tune and music of Cigarette Cases Dance. The music starts off depicting the beautiful scenery of Southwest China where the tribe resides. As music proceeds, we hear the songs that they sing to each other to convey their love and young people gather dancing at the festival.

Originally composed for soprano and pipa, the music conveys a sense of timelessness and meditation.

Globalization of the Pipa

As the pipa enters global concert spaces, composers experiment with new idioms and ensemble settings. A wave of Chinese composers, including but not limited to Zhou Long, Chen Yi, Tan Dun, and Bright Sheng, pursued higher degrees and eventually moved abroad after the end of the Cultural Revolution. And they continue to compose music for Chinese instruments including the pipa. Examples include Ghost Opera by Tan Dun, Green by Zhou Long, and Point by Chen Yi. Many contemporary composers of different ethnicities also composed new and exciting music for the instrument, including Terry Riley (The Cusp of Magic) and Philip Glass (Orion). Wan’s collaborations include world premieres, interdisciplinary projects, and duo performances that highlight the pipa’s expressive range in a modern context.

Original Music

Autumn Moon (2012)

The music of Autumn Moon (2012) utilizes the pentatonic scale that we now identify as the Japanese Hirajoshi scale. But similar scales were present in Chinese music during the Tang Dynasty (618 CE - 907 CE), when the pipa was one of the most prominent court instruments.

Artwork by Paul Binnie featured in the accompanying video:

References

- Chan, Sau-yan. 1991. Improvisation in a Ritual Context: The Music of Cantonese Opera. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press.

- Chen, Zhengsheng 陳正生. 2022. “Chunjiang Huayueye de ‘qianshi’ ‘jinsheng’《春江花月夜》的‘前世’‘今生’ (The ‘Past Life’ and ‘Present Life’ of Chunjiang Huayueye).” Huain 華音網, February 28, 2022. https://www.huain.com/article/composer/2022/0228/551.html

- Han, Kuo-Huang. 1978. “The Chinese Concept of Program Music.” Asian Music 10 (1): 17–38.

- Jia, Yi 賈怡. 2007. “'Xi' wai, chuan ling: Ping Cheng Wujia shier pingjunlü liu xiang shiba pin pipa gai 『西』外, 傳靈: 評程午加十二平均律六相十八品琵琶改 (‘Westernized’ Look and Traditional Soul: On Cheng Wujia’s Six Xiangs and Eighteen Pins Pipa Reform Based on Twelve-tone Equal Temperament).” Hundred Schools in Art 96 (3): 108–109.

- Lai, Kin 黎鍵. 2010. Xianggang Yueju Xulun 香港粵劇敘論 (Narration of Cantonese Opera in Hong Kong). Hong Kong: Joint Publishing (H.K.).

- Li, Jinsong 李勁松. 2007. “Dui Wude yanbian dao pipa de wenhua yueshi 對烏德演變到琵琶的文化閱釋 (The Cultural Interpretation of the Transformation of the Oud to the Pipa).” Hundred Schools in Art 97 (4): 124–125.

- Liu, Wei-hua 劉芛華. 2021. “Chuantong pipa yuequ fenlei zhi tantao 傳統琵琶樂曲分類之探討 (An Investigative Study on the Traditional Classification of Classic Pipa Scores).” Yinyue Yanjiu 音樂研究 (Music Research) 34: 63–93. https://doi.org/10.6244/JOMR.202105_(34).03

- Myers, John. 1992. The Way of the Pipa: Structure and Imagery in Chinese Lute Music. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press.

- Picken, Laurence. 1955. "The Origin of the Short Lute.” The Galpin Society Journal 8: 32–42.

- Sotomura, Ataru. 2010. “Tangdai pipa zakao 唐代琵琶雜考 (Tang Pipa Examined).” Trans. Li Fei. Ed. Zhao Weiping. Yinyue Yishu 音樂藝術, Journal of the Shanghai Conservatory of Music 2: 59–70.

- Yang, Mina. 2007. “East Meets West in the Concert Hall: Asians and Classical Music in the Century of Imperialism, Post-Colonialism, and Multiculturalism.” Asian Music 38 (1): 1–30.

- Yeung, Ngai Wan. 2024. "Becoming One Country, One System: Cantonese Opera in Post-Colonial Hong Kong." PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles.

- Yu, Mo Wan 余慕雲. 1987. "Xianggang Yueju Dianying Fazhan Shihua" 香港粵劇電影發展史話(History of Hong Kong Cantonese Opera Movies). In The 11th Hong Kong International Film Festival: Cantonese Opera Film Retrospective. Hong Kong: Urban Council. 20.

- Yu, Siu Wah. 2014. "Ng Wing Mui (Mui Yee) and the Revival of the Sineung (Blind Female) Singing Style in Cantonese Naamyam (Southern Tone)". CHINOPERL 33 (2): 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1179/0193777414z.00000000023.

- Yung, Bell. 1989. Cantonese Opera: Performance as Creative Process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.